We shot these images on April 27, 2003 at Austn's Chain Drive bar. BigPJ had never worn leather before and he was loving it. There are more in the series using a corrugated metal wall background. Let me know if you want to see them…

He was a real trooper. Posing on the motorcycle at the bar was a lot of fun. For both of us.

BigPJ & World of leather: how Tom of Finland created a legendary gay aesthetic

His subversive drawings ridiculed authority figures and inspired the look of Freddie Mercury and the Village People. A new film tells the story of Touko Laaksonen’s rise to become Europe’s kinkiest art export. By Alex Needham

Via The Guardian

While sex between men was partially decriminalised 50 years ago in the UK, in Finland it took until 1971. And it wasn’t until very recently that the Finns were relaxed enough about homosexuality to openly acknowledge one of their country’s most famous exports. In 2014, they put his unmistakably erotic artwork on a set of stamps; this year, a biopic became a mainstream hit at the nation’s multiplexes. Almost 100 years after his birth in the town of Kaarina, Tom of Finland had come home.

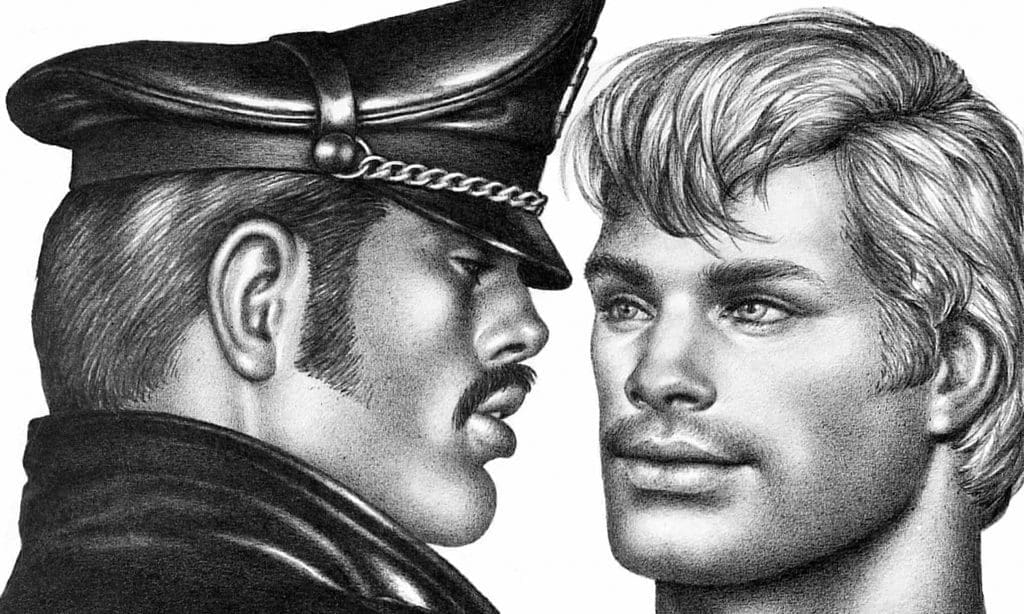

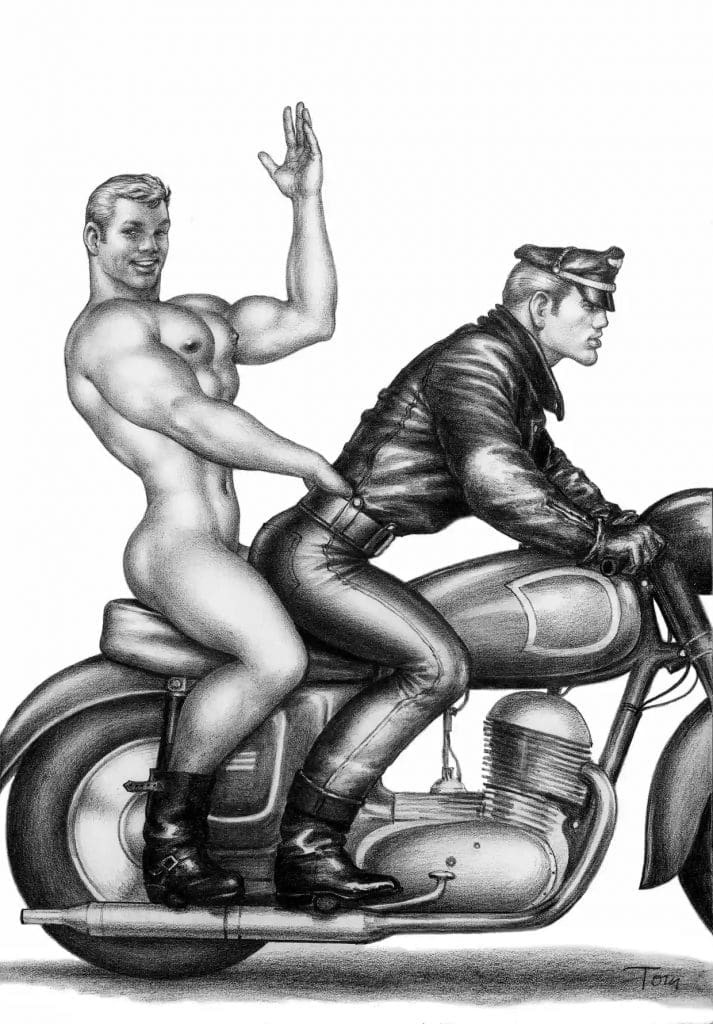

Tom’s real name was Touko Laaksonen. By day, he was a senior art director at advertising agency McCann Erickson. In his spare time, however, Laaksonen drew his sexual fantasies – bikers and lumberjacks, mounties and policemen going at it hammer and tongs in forests, prisons and parks, the smiles on their faces almost as big as their enormously tumescent penises. Initially published in American gay proto-porn magazines such as Physique Pictorial, they were disseminated worldwide in dime stores, sex shops or leather bars through an international underground of fans, despite laws against the distribution of such explicit material.Homoerotic artist Tom of Finland gets the official stamp of approvalRead more

Laaksonen’s pictures fuelled both the sexual fantasies and the aesthetic of many gay men. The fetish for police and military uniforms and the leather-clad look – often including a cap, chaps and biker jacket – worn by Freddie Mercury, Frankie Goes to Hollywood and, of course, Glenn Hughes, the leatherman from the Village People, was directly inspired by his work. Initially drawing men in riding breeches and army officers in brown leather bomber jackets, he got into the biker look after seeing Marlon Brando in The Wild One. Thereafter, says Durk Dehner, a Canadian friend of Laaksonen’s and now the custodian of his work, Laaksonen and the nascent gay leather scene would inspire one another. Laaksonen would draw his fantasies and send them to friends. They would get a tailor to replicate the sexiest garments in the pictures, photograph themselves in them, and send the pictures back to the artist. “Then he’d get more ideas – it was evolving,” says Dehner.

Yet, while they were avowedly pornographic, there was a subversion to the images, too. The scenarios, in which macho authority figures abandon themselves without shame to kinky group sex, provided not just arousal but also humour, affirmation and pride for a then frequently despised minority. “In his drawings he’s basically ridiculing the authorities,” says Dome Karukoski, director of the Tom of Finland film. “The cops are beating [gays] in the park and then he’s inviting them for sex.”

“What he represents to us is freedom,” says Dehner. Dressed in a leather suit and tie when we meet on a warm afternoon in London, he runs the Tom of Finland Foundation, which is based in his and Laaksonen’s house in the Echo Park district of Los Angeles. “There was a French contemporary photographer I saw at an exhibition of Tom’s work and she was radiant. I asked her to share what she was feeling and she said: ‘Here’s a man who did not inhibit what was in his heart.’” Or, indeed, his pants.

While Laaksonen’s fantasies were fuelled by his experiences in the second world war (the Finns fought on the side of the Nazis; although he despised the ideology, Laaksonen admitted to loving the jackboots), he was anti-racist, depicting interracial gay couplings when they were completely taboo. “I think it’s good to look at the more progressive aspects of his work, like if the black guy fucked the cop then this is literally fuck the police, and we’re talking the 1950s,” says Stefan Kalmár, director of the ICA in London, who put on a Tom of Finland exhibition two years ago at his previous gallery, Artists Space in New York. “It’s hard to comprehend what it meant to see male stereotypes so – for a want of a better word – perverted.”

It’s this playful rebelliousness that has made Laaksonen’s work resonate beyond the audience for which it was intended. “In Finland, you can see 15-year-old girls walking around with Tom of Finland T-shirts,” says Karukoski. “It’s cool, it’s sexy, it’s edgy, the drawings are magnificent – there’s something about the attitude that also entices young women.” The audience for his film, he says, was 65% female. Dehner says that when he drove around town in a car emblazoned with his drawings for a gay pride parade, “the No 1 type of person that would want to be photographed with it was women between 20 and 30”.

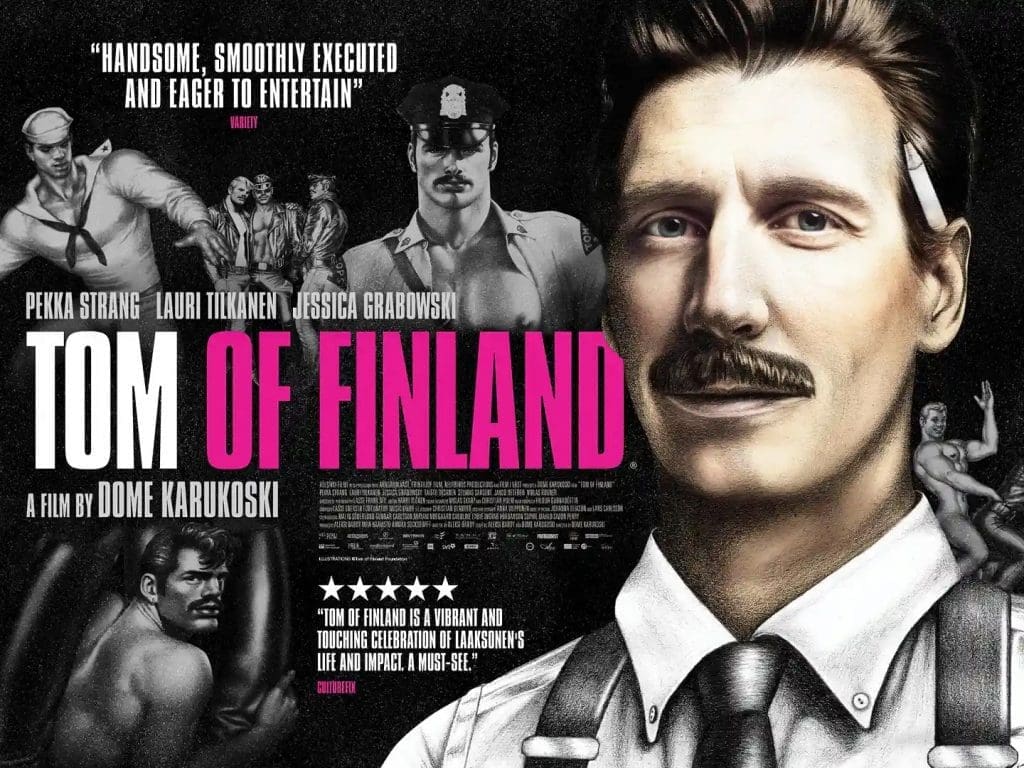

Unlike many of his friends, Laaksonen weathered the Aids crisis, but he died of emphysema in 1991, aged 71. He had been unknown to most Finns until his obituary appeared in the Helsinki Times. An hour-long documentary, Tom of Finland: Daddy and the Muscle Academy, came out shortly after his death; now the artist’s story has been told in Karukoski’s film. Starring Pekka Strang in what the Finnish actor describes as “the role of a lifetime”, the film takes us from Laaksonen’s formative time in the army to his later years as a cult hero. “It’s almost a Superman story, where the Clark Kent that works in an ad agency wearing a suit comes to LA and puts his leather gear on – the hero’s arrived!” says Karukoski.

Like Laaksonen, Karukoski is Finnish; very much unlike the artist, he is heterosexual (as is Strang), although he tried hard to get in the right frame of mind. “In a way, [making the film] was me just watching very hot guys for five years,” says the director. “I look at a man differently now. I see different elements in his beauty, his sexuality. Of course I would never understand the appraisal of the dick in an erotic way, but then again …”

Considering the film’s subject matter, it actually contains very little sex – the main bedroom scene cuts from a kiss to the morning after. “The core fans were always saying: ‘I’ve seen the drawings, those are my sex, now I want to see the story of the man I idolise,’” says Karukoski. “So the amount of gay sex will come very much from the dramatic need. Where is the line where it becomes provocation? [When] it overrides the emotional balance of the story.”

Instead, much of the film focuses on the struggles Laaksonen endured as a gay man in conservative Finland, from facing jail as a young man after a pick-up went awry, to facing constant pressure from his younger sister never to express his true identity, since she believed it would bring shame on the family. “Even when I told her about him being accepted into the permanent collection at MoMA, her response was: ‘Well, what were they thinking?’” says Dehner, still hurt by the memory. The film, he says, is “touching – how terrible society has been to us and how conditional the love is from family members”.

Dehner fell in love with Laaksonen’s work aged 26 when he saw it in a New York leather bar. He wrote a fan letter inviting him to the US, where he knew Laaksonen’s images would find a devoted audience. He became, he says, Laaksonen’s “business partner, his publicist, his best friend, his confidant, his muse, his pimp, his sex partner”. Although not life partner – that was Finnish dancer Veli Mäkinen, with whom the artist spent 28 years until Mäkinen’s death from throat cancer in 1981, and whose story is explored in Karukoski’s film.

In LA, “Tom got to be part of a brotherhood,” Dehner says. “He wasn’t held in awe, he got to be one of the boys and he loved that part.” Not that he didn’t get some special treatment. “When he had his first exhibition in New York, in Stompers Boots, we picked him up at the airport and he was in his tweed suit,” Dehner remembers. “Then he got into a Lincoln, a beat-up one, but we had a motorcycle escort into Manhattan as the sun was setting. He changed in the back seat into his leathers, and we had a gin and tonic waiting for him because that was his drink.”

Andy Warhol attended that first exhibition in a boot shop, in 1978, while Robert Mapplethorpe owned some of his work – he and Laaksonen were friends. Laaksonen’s pictures were also admired by straight artists such as Raymond Pettibon and Mike Kelley who picked up on the tension between its sunny appeal – Laaksonen, after all, was an ad man – and its transgressive subject matter.

“It’s essentially outsider art, and yet how can someone who works for one of the biggest global companies do outsider art?” says Kalmár about the work’s ambiguity and the way, pre-internet, it found a worldwide audience. “How can one man create such iconic images that are a bit like Walt Disney and be known around the globe? You can probably go to a village in China and they will have heard of Tom of Finland.”

Then there’s the jaw-dropping nature of those gigantic penises. Karukoski clearly remembers his first viewing of Laaksonen’s work at school when he was about 12. “Someone had nicked or found his comic books. We were too young to understand sexuality in any form, I think our wildest dream was Samantha Fox Strip Poker on the Commodore 64. We were looking at it behind the school, and we were like: ‘Do the dicks really grow so big?’”

It’s perhaps this combination of stylish technique and outrageous content that makes Laaksonen’s work so potent. The Tom of Finland stamps issued by the Finnish postal service in 2014 were a runaway hit: orders flooded in from 154 different countries for the chance to lick a stamp adorned with a picture of a naked male bottom, with Laaksonen’s hero and alter ego Kake’s face peering between the muscular thighs. “Finns absolutely love the fact that they could mail a postcard to someone they knew in Russia with a butt on it,” Dehner says. “Of course Tom would have been tickled.”Tom of Finland review – intriguing biopic of a gay liberation heroRead more

He says his main issue with the film, on which Dehner was a consultant but had no artistic control, is that Strang doesn’t smile enough – “He smiled a whole bunch more.” Laaksonen “was understated but not insecure at all, very self-assured and humour was a big part,” Dehner says. Then there’s the styling: “I think that Tom’s leathers could have fitted him a little tighter, a little better in the film. Jean Paul Gaultier whispered in my ear at the premiere: ‘If you do another production, please ask me to be involved.’”

Dehner’s dream is for a Broadway musical about Laaksonen’s life to be staged, ideally with a gay creative team. In the meantime, he nurtures gay artists at the Tom of Finland Foundation, where they can stay at the house and make work; a biennial erotic art contest has lured judges including Helmut Lang and Elmgreen and Dragset. The Foundation serves as a base where Dehner can disseminate and promote Laaksonen’s work, not just to metropolitan centres such as London and New York, but to much less gay-friendly places including Riga in Latvia, which hosted a Tom of Finland exhibition a couple of years ago.

Called Tom’s House, the Foundation’s interior is crammed with Laaksonen’s old drawings and decor. Even the armchair cushion comes adorned with a phallus; a temple to one man’s sexual fantasies. In true Laaksonen style, it also boasts a dungeon, a must-visit for Tom’s international army of lovers, still gathering new recruits. As Karukoski tells me: “I’m sure if you want to they can show you the games.”